When I first started preaching in rural areas, I was surprised at the centrality of revivals to rural church culture. They are frequent, plentiful, and well-attended. You may occasionally see revivals in the city or suburbs, but more often they are “conferences,” or “seminars,” aimed at people already attached to the movement. Out away from the city, the pitch is still basically “come and get saved.” It’s refreshingly simple.

I have actually preached one of these revivals, which is not a sentence many Presbyterian clergy can write anymore. It was, admittedly, a small one which I began with the sentence, “This is not a revival.” We sang old hymns and had no altar call, but it was an honest attempt at popular, evangelistic preaching in a Presbyterian church for the community. It was also, by a wide margin, the largest crowd I have spoken to since I started preaching out in the country.

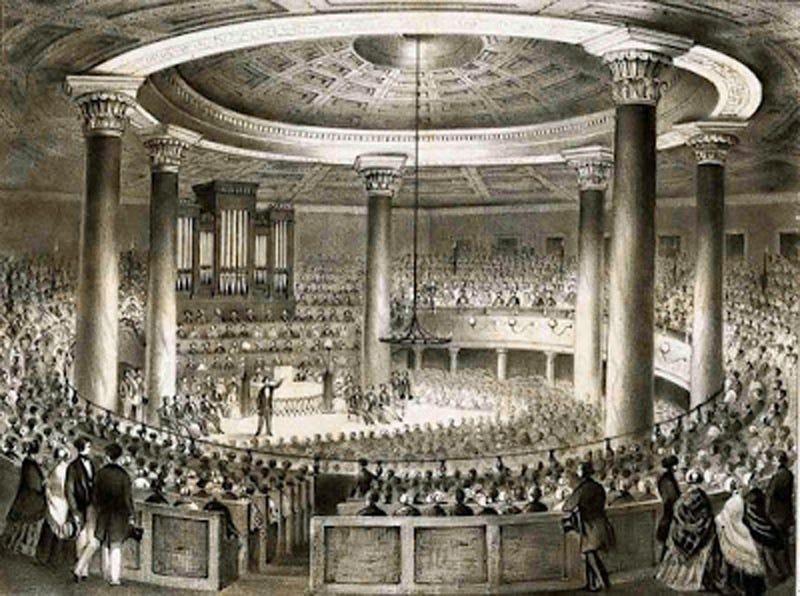

Our meager attempts excepted, most country revivals would make Finney proud with the psychological manipulation they bring to bear. The standard form is essentially a “set” by a local band (often the worship band from the host church), followed by a rousing and excitable message, and closed with a protracted altar call. It’s a reliable formula - start working up a trance state with the music, induce increasing anxiety with aggressive preaching verging on yelling, and land with a strong call to action that gives the potential of cathartic release, all with a strong dose of peer pressure to back it up. It’s no surprise that people come forward at these, and it’s no surprise that most of the response is short-lived and insincere. It’s not an act of God, after all. It’s an act of psychological coercion.

So why am I still in favor of revivals (or something like them)?

The short answer is that they are an attempt, however flawed, at reaching the general public without twisting congregational worship into something it is not and cannot be.

The current worship landscape of the American church breaks down essentially into two camps - revivalistic churches and shepherding churches. Revivalistic churches view the primary goal of gathered worship to be the conversion of unbelievers to Christianity. Good examples of this would be the megachurch that builds everything around relevance, or the old-timey fundamentalist church that wraps up every service with an altar call. Shepherding churches view the primary goal of gathered worship to be the tending and feeding of believers with the ordinary means of grace. Most Reformed churches fall into this column, with their focus on preaching as the central act of worship, but also more liturgical and sacramental traditions, such Roman Catholic or Episcopal, or even the more low-key approach of many mainline churches.

To put my cards on the table, the shepherding churches are biblically correct. The gathered worship of the church is for believers.

“And let us consider how to stir up one another to love and good works, not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another, and all the more as you see the Day drawing near.” (Hebrews 10:24-25, ESV)

Worship is the fundamental act of this “meeting together,” and the exhortation here is clearly for believers to come together.

Even the first description of worship after Pentecost follows this approach:

"And they devoted themselves to the apostles' teaching and the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers." (Acts 2:42, ESV)

Worship is for believers. We are pleased when unbelievers come into that worship, are convicted, and become believers (such as in 1 Corinthians 14), but that is not the point of worship.

The errors in the revivalistic churches spin out of failing to recognize that worship is for believers. Instead, since their core desire is to bring outsiders into Christianity, they allow unbelievers to define the terms of worship. When the salvation of sinners becomes the center of public worship, it leads to all the distortions we’ve seen in recent years: watered-down preaching, obsession with relevance, mocking tradition, pandering to the culture, and even compromise on important issues. All the gross Andy Stanley “unhitching” the church from the Bible and the Old Testament in particular is the inevitable result of the method.

Because revivalistic churches have seen the power and importance of evangelism, they generally believe that the optimal state of the church is to exist in a kind of never-ending revival. They build their services to accomplish, or at least to simulate this ideal reality. Every service wants to be the start of a new outbreak of the Spirit, and when that’s what you yearn for, week after week, it’s unsurprising that you convince yourself it’s happening every now and then.

This being said, the revivalistic churches have remembered something many of us in shepherding churches have forgotten: the burden Christians must have for the lost. If our savior came to seek and save the lost (Luke 19:10), we are called to have the same mission. The apostles went to tremendous lengths to reach lost, damned sinners, but we, in our comfortable pews, will not even tolerate the mild social disapproval that comes from straightforward witnessing. Their heart is admirable, and in many ways, far superior to ours. Their refusal to accept doctrinal and historical restraint has done damage to the church, but their zeal puts us to shame.

The method of growth among shepherding churches is actually quite simple: as people realize that their revivalistic churches are only giving them thin gruel, they come looking for more substantial fare and find it in our pastures. I am not suggesting this is an illegitimate method of growth. Scripture speaks volumes, and the great commission calls the church to teach disciples “all that I have commanded you.” Churches that refuse to do this deserve to wither and be judged for their disobedience. I am suggesting that, since we have used revivalistic churches as our farm team, this has twisted shepherding churches into something nearly unrecognizable from biblical Christianity. We have almost completely given up the task of evangelism.

Many in my camp will protest this accusation. We all say we know how important evangelism is. We all try to make the gospel message clear in our sermons. We all, often, make the clear application that unbelievers need to repent and be saved, and in our wilder moments, set aside someone to pray with anyone who might respond in such a manner after the service. These are all good things, but I will wager good money that, if you survey your congregation, virtually no one who wasn’t born in the church came to faith through these efforts. No one who grew up outside the church comes to faith in a shepherding church. You can find your anecdotal evidence that shows the exception, but exceptions are exceptions. Their oddity proves the rule.

This is precisely why we need to bring back the revival, or if that name sticks in your craw, call them popular meetings, mass meetings, evangelistic rallies, or whatever clever marketing gimmick you can conjure up. Let us bring back popular evangelistic preaching in our circles, and not just let the revivalists do it for us. As long as we only get new people through revivalistic churches, we will remain fixers, not evangelists. There is something in the heart of the Christian that becomes increasingly deformed the more isolated he is from the evangelical task. If you see how ivory-tower academics, political elites, and mainstream media have completely misread the mood of the nation, precisely the same thing will (and does) happen to us in our churches when we stop speaking to the people around us.

Lots of good points in here - thanks for writing!